How Does a Sailboat Actually Move?

Sailing is a fascinating dance with the elements, a subtle harmony between the wind, the water, and the boat. For the uninitiated, watching a sailboat slice through the waves, especially against the wind, can seem like magic. Yet, behind this apparent sorcery lies precise science and age-old expertise: the mastery of the points of sail. Understanding how a sailboat works is the essential first step for any aspiring sailor eager to set out on the water. Indeed, it is this knowledge that allows a sailor to transform the raw power of the wind into controlled, efficient propulsion. This article aims to guide you, step by step, into the world of sailing’s points of sail. Furthermore, we will demystify the physical principles that allow a sailboat to move forward. In the end, whether you are a future skipper or simply a curious sea lover, this complete guide will give you all the keys to understanding how a sailboat works.

How a Sailboat Works : Sailing isn’t just about hoisting

The sails and letting the wind do all the work. On the contrary, it is an art that demands observation, anticipation, and a deep understanding of your boat’s behavior. Every direction a sailboat takes relative to the wind has a name; this is what we call a “point of sail.” Consequently, knowing how to identify and master these different points of sail is fundamental to steering your vessel safely and effectively. First, we will cover the basics of sail propulsion, explaining the forces at play in simple terms. Then, we will detail each point of sail, from close-hauled to running, with the help of a clear wind rose infographic. Additionally, we will explore how to optimize speed and comfort based on the chosen point of sail. In short, prepare to embark on a journey into the heart of sailing mechanics—an adventure that will reveal how humanity learned to tame the wind to explore the oceans.

The Fundamentals of Understanding How a Sailboat Works: Push vs. Pull

Before diving into the details of the different points of sail, it is crucial to grasp the two main principles that allow a sailboat to move. Although it may sound complex, the concepts of push and pull (or lift) are actually quite intuitive. Thus, understanding them is the foundation upon which all sailing logic is built.

The Push: The Art of Being Carried by the Wind

The first force, and the most obvious one, is the push. Imagine holding an open umbrella in a strong wind; you feel a force pushing you backward. Similarly, when a sailboat is on a downwind course (the “running” or “broad reach” points of sail), its sails billow out and act like giant parachutes. The wind, filling the sails, exerts direct pressure that literally “pushes” the boat forward. This is why this force is particularly dominant when sailing with the wind behind you. However, the push alone cannot explain how a sailboat can travel upwind. For that, we need to introduce a second, more subtle, but equally powerful force.

The Pull (Lift): The Secret to Sailing Against the Wind

This is where the real “magic” happens. To grasp understanding how a sailboat works when heading into the wind, we must look at the principle of lift—a phenomenon similar to what allows an airplane’s wings to make it fly. When a sailboat is sailing “close-hauled,” meaning as close to the wind direction as possible, the sails are not simply being pushed. In reality, they are acting like a vertical wing.

The wind splits into two streams as it hits the sail. The stream of air traveling along the outside of the sail (the leeward side, which is curved) has a longer distance to travel than the stream moving along the inside (the windward side). Therefore, for both streams to rejoin at the back edge of the sail at the same time, the outside stream must accelerate. According to Bernoulli’s principle, this acceleration creates a low-pressure zone, a kind of suction. Simultaneously, on the inside of the sail, the slower-moving air creates a high-pressure zone. The pressure difference between the two sides of the sail generates a force perpendicular to the sail: this is lift. It is this force that “pulls” the sailboat forward and sideways.

So, why doesn’t the boat just slide sideways? This is where the boat’s underwater profile, specifically its keel or centerboard, comes into play. This submerged fin resists the sideways force (leeway), allowing only the forward component of the lift to propel the boat ahead. Thus, thanks to the power of lift, a sailboat can not only move forward but can also sail at an angle of about 45 degrees into the wind.

The Wind Rose: An Essential Sailor’s Tool

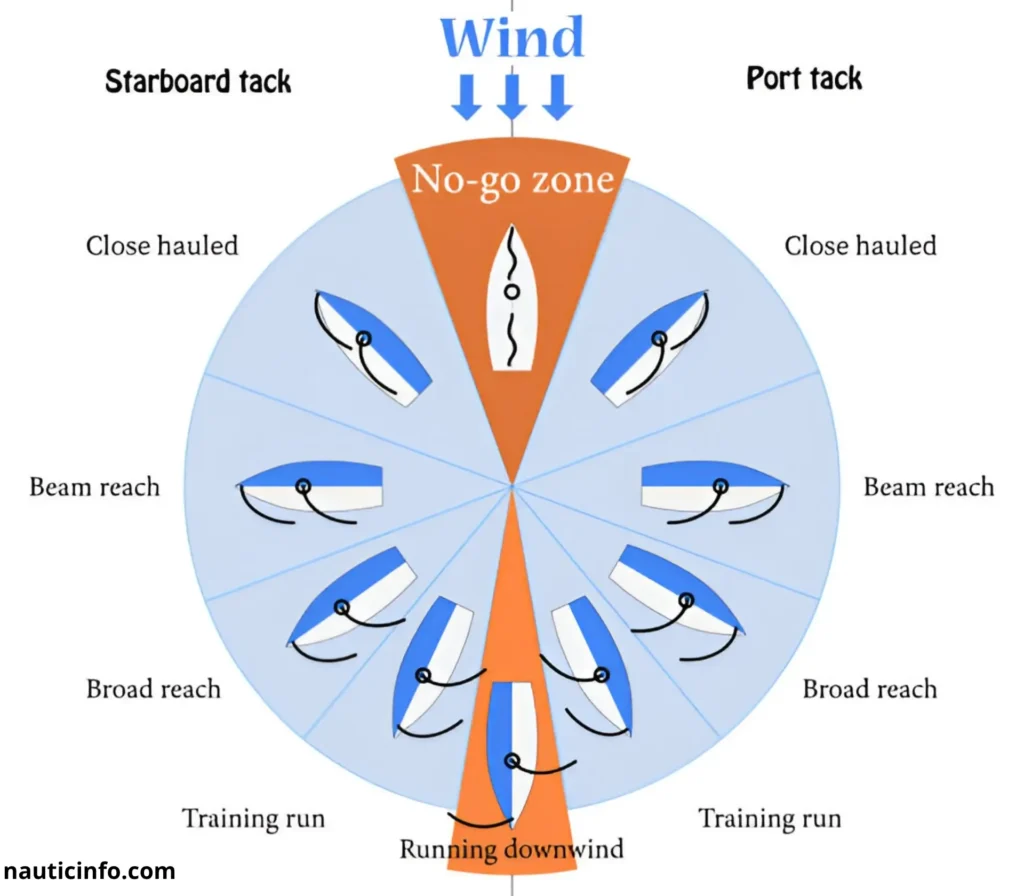

To visualize and understand the points of sail, sailors use a diagram called a wind rose. It’s a schematic that shows the direction of the wind and the different navigable zones for a sailboat relative to that wind.

- At the center of the image: A circle representing the 360° of the horizon.

- An arrow pointing down from the top: This indicates the “True Wind Direction.”

- A conical zone at the top (facing the wind): Colored in red and labeled “In Irons” or “No-Sail Zone” (approximately 45° on either side of the wind’s axis). In this zone, a sailboat cannot generate power and its sails will flap uselessly (luff).

- On either side of the red zone: Two sectors labeled “Close-Hauled” (from roughly 45° to 60° off the wind). Each sector shows a sailboat heeling over with its sails pulled in tight (sheeted in).

- Below the Close-Hauled sectors: Two sectors labeled “Beam Reach” (at 90° to the wind). The sailboats are shown more upright, with sails let out slightly.

- Further down: Two sectors labeled “Broad Reach” (from roughly 120° to 150° off the wind). The sailboats are depicted with their sails well out, catching the wind’s push.

- The bottommost sector: Labeled “Running” (at 180° to the wind). A sailboat is shown with its mainsail on one side and its headsail (jib or genoa) on the other, a configuration known as “wing-on-wing.”

This infographic allows a sailor to understand, at a glance, the boat’s position relative to the wind and the corresponding point of sail.

Sail Trim Mastery: The Key to Optimizing Points of Sail

Understanding points of sail is incomplete without proper sail adjustment. Follow this golden rule: The higher you sail toward wind (close-hauled/reach), the more you trim in sails. The lower you sail (broad reach/run), the more you ease out sails. Use this quick reference:

| Point of Sail | True Wind Angle | Mainsail Trim | Headsail Trim | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close-Hauled | 45°-60° | Sheeted hard, traveler up | Sheeted tight, lead forward | Maximize upwind angle |

| Close Reach | 60°-80° | Firm trim, traveler mid | Firm trim, lead mid | Balance speed/angle |

| Beam Reach | 80°-110° | Moderately eased | Moderately eased | Maximize speed |

| Broad Reach | 110°-160° | Eased, preventer set | Eased broadly | Stability & control |

| Run | 160°-180° | Fully eased, wing-on-wing | Spinnaker/pole | Avoid gybes |

Always fine-tune: Watch for luffing or stalled airflow using tell tales (yarn on sails). They must stream backward for optimal flow.

A Detailed Guide to Understanding How a Sailboat Works on Each Point of Sail

Now that the fundamentals are established and we have a mental image of the wind rose, let’s explore each point of sail in detail. Each one has its own characteristics, specific sail trim, and unique feel.

Close-Hauled: The Art of Sailing Upwind

Sailing close-hauled means heading as close to the wind as you can. It is undoubtedly the most technical point of sail, but also one of the most rewarding.

Understanding how a sailboat works when close-hauled

Sailors often distinguish between “pinching” (or sailing high) and “footing” (or sailing fast). Pinching allows you to gain the most ground directly upwind (making a better “Velocity Made Good,” or VMG). But often at the cost of speed. Conversely, footing off slightly from the wind allows you to build speed and comfort. Even if you sacrifice some upwind angle. For this reason, the choice between these two modes depends on your sailing strategy, the sea state, and the type of boat. The sails are sheeted in as tightly as possible to create a flat, efficient airfoil, thereby maximizing lift. This is a point of sail where the boat heels (leans over), offering thrilling sensations but which can be uncomfortable in choppy seas.

Beam Reach: Pure, Unadulterated Speed

When the wind comes from directly over the side of the boat (at a 90° angle), you are sailing on a beam reach. This is often the fastest point of sail for a typical cruising sailboat.

Understanding how a sailboat works on a beam reach

On a beam reach, the boat benefits from an excellent combination of lift and push. The sails are eased out (let out) compared to being close-hauled, allowing them to capture the wind optimally. The heel is generally moderate, and the boat glides across the water with remarkable stability. As a result, it is a very pleasant and efficient point of sail. Often favored for long passages when the destination allows for it. Sail trim is less critical than when close-hauled, making it more forgiving for beginners.

Broad Reach: The Comfortable Glide

As you bear away further from the wind, you enter the downwind points of sail, starting with the broad reach. The wind now comes from the rear quarter of the boat (between 120° and 150°).

Understanding how a sailboat works on a broad reach

On a broad reach, the pushing force of the wind becomes dominant. The sails are let out wide to present maximum surface area to the wind. The boat accelerates significantly, and it is on this point of sail that you might choose to fly downwind sails like a spinnaker or gennaker to add even more sail area and speed. Sailing is generally very comfortable, with little heel and a gentle rolling motion. Sailors sometimes differentiate between a “close reach” (closer to a beam reach) and a “broad reach” (closer to running downwind). With the latter often synonymous with exhilarating bursts of speed and surfing down waves.

Running: Sailing Directly Downwind

This is the point of sail where the wind comes from directly behind the boat (180°). It is the most intuitive direction, the one most people picture when they think of a sailboat.

Understanding how a sailboat works when running downwind

Although it seems the simplest, running downwind requires special attention. Indeed, the boat can become unstable and prone to rolling. Furthermore, a major danger awaits the inattentive sailor: the accidental jibe (or gybe). If the wind suddenly catches the back of the mainsail. The sail and its boom (the horizontal spar at the bottom) can swing violently across the cockpit. Posing a serious risk to the crew and equipment. To mitigate this risk, it is often safer to sail on a broad reach rather than a dead run. Another technique is to set the sails “wing-on-wing”: the mainsail on one side and the headsail on the other. Often held out with a whisker pole. This configuration provides better stability and exposes a large, effective sail area to the wind.

Understanding How a Sailboat Works : Maneuvers and Transitions, The Art of Changing Course

To move from one point of sail to another or to change direction relative to the wind, a sailor must perform specific maneuvers. The two basic maneuvers are tacking and jibing.

Changing Direction into the Wind

Tacking is the maneuver used to change your course by turning the bow of the boat through the wind. For example, if you are sailing on a close-hauled course on a starboard tack (wind coming over the right side), you will tack to end up on a close-hauled course on a port tack (wind coming over the left side). To do this, the helmsman announces “Ready to tack?” to ensure the crew is prepared. Then, they will call “Helms a-lee!” and turn the boat into the wind. The boat passes through the “in irons” or “no-sail zone,” where the sails luff, and then the wind fills the sails on the opposite side. The crew must then quickly trim the jib or genoa sheets on the new side. This is a fundamental maneuver, especially for making progress upwind in a zigzag pattern (known as “beating”).

Jibing (or Gybing): Changing Direction with the Wind

A jibe is the equivalent of a tack but for downwind sailing. You change tacks by turning the stern of the boat through the wind. The helmsman announces “Prepare to jibe?”. The maneuver involves swinging the stern through the wind, causing the sails to shift from one side to the other. As mentioned, the boom’s passage can be violent. Therefore, the maneuver must be controlled by sheeting in the mainsail right before the stern crosses the wind, and then easing it out smoothly on the new side. Good crew coordination is essential for a safe jibe.

Conclusion: Understanding How a Sailboat Works—A Lifelong Journey

Understanding how a sailboat works is not just about technical skill; it is about entering an intimate conversation with the wind and sea. We have seen that a sailboat’s propulsion relies on two complementary forces—push and lift—that allow it not only to be carried by the wind but also to sail against it. Each point of sail, from close-hauled to running, has its own logic, its own trim, and its own feel. Close-hauled sailing demands finesse and concentration to claw your way upwind. The beam reach offers the quintessence of speed in perfect balance. Finally, the broad reach and running provide sensations of gliding power, while demanding constant vigilance.

The wind rose

Has served as our compass through these concepts, clearly illustrating how the angle between the boat and the wind defines how you sail. Furthermore, mastering maneuvers like tacking and jibing is what allows a sailor to connect these points of sail together to chart a course to any destination.

Ultimately, this world is much more than a simple set of physical rules. It is an invitation to observe and listen to the elements. Learning to trim your sails to the very edge of luffing, feeling the boat accelerate in a gust, anticipating a wave to ease the hull’s motion… all of this is part of the continuous learning process that makes sailing so captivating. So, whether you are about to sign up for your first sailing lesson or are just dreaming of distant horizons, remember that every gust of wind is an opportunity. An opportunity to understand, to learn, and, finally, to move forward. Because that is the true beauty of sailing: a perpetual quest for harmony to glide across the water, propelled by the most natural force there is.